Send a written request to the council’s private sector housing or environmental health team asking for an inspection date and a clear reason if they will not attend. If nothing is done, the disrepair or hazard usually continues and the landlord’s position hardens because there is no official record. Keep the request factual, attach a small set of evidence, and ask for the case to be logged and acknowledged. If the refusal is informal (phone call or vague email), ask for it in writing so the next escalation is straightforward.

What the problem is

This comes up in UK private renting when a tenant reports hazards such as damp, mould, unsafe electrics, broken heating, pests, or serious disrepair and expects the council to inspect. It often affects people in flats and HMOs, but it also happens in single-family lets where the landlord is slow to act and the tenant needs an independent record. The sticking point usually appears after the tenant has already complained to the landlord or agent, has waited for promised repairs, and then contacts the council for help. A common trigger is receiving a brief reply saying the council will not inspect, will only offer advice, or will only act if the tenant can prove an “immediate risk”.

Refusals are often not a formal decision; they can be a triage response, a closed case without explanation, or a request to “keep working with the landlord”. The practical problem is that without an inspection or a logged assessment, it becomes harder to push repairs, challenge rent deductions, or show that the issue is not just a minor inconvenience. It can also leave the tenant unsure whether to keep chasing the council, switch strategy, or escalate to a different route.

Why this happens

Councils prioritise cases based on risk, vulnerability, and the likelihood that enforcement action will be proportionate. Where the report looks like a routine repair, a long-running dispute, or something that might be resolved by the landlord without intervention, the case can be screened out. Some councils also rely heavily on remote triage, asking for photos, videos, or a landlord’s response before deciding whether a visit is necessary.

Another common cause is the way the report is framed: if the initial contact focuses on inconvenience rather than hazard, or lacks dates and evidence, it can be treated as low priority. If the landlord has provided a partial response (for example, a dehumidifier, a promise of a contractor, or a single patch repair), the council may decide to wait and see rather than inspect immediately. A typical organisational response pattern is that the first reply is a standard template asking for more information and suggesting the tenant continues with the landlord before the case is reviewed again.

There is also an incentive issue. An inspection can lead to formal steps that require officer time, follow-up visits, and legal work, so teams tend to reserve inspections for cases that are clearly within scope and well evidenced. That does not mean the problem is not serious; it means the report needs to be presented in a way that fits the council’s decision process.

Your rights in practice

In UK renting, the practical leverage comes from showing that the issue is a hazard affecting health or safety, that the landlord has had a fair chance to fix it, and that the council has enough information to justify an inspection. Councils are not obliged to act on every complaint in the same way, but they are expected to consider reports properly and follow their own procedures. A refusal that is vague, inconsistent, or not based on the facts can often be shifted by asking for a written decision, the reason, and the criteria used.

What usually works is making the request easy to process: a short timeline, clear symptoms, and evidence that links the condition to a risk (for example, persistent mould in a bedroom affecting breathing, or no fixed heating in winter). If the landlord is ignoring written requests, that matters because it shows informal resolution has failed. If the landlord is offering access only on unreasonable terms, that matters because it explains why the issue is stuck.

It also helps to be clear about what is being asked for. Asking for “an inspection and written outcome” is more actionable than asking for “help”. Asking the council to confirm whether the report has been logged as a housing standards complaint, and to confirm the next review date, often prompts a more concrete response.

Official basis in UK

The practical route is the council’s Housing Health and Safety Rating System (HHSRS) approach, which is the framework councils use to assess hazards in rented homes and decide whether enforcement action is appropriate. In day-to-day terms, this means the council looks at the condition, considers who is exposed and how, and then decides whether to inspect, write to the landlord, or take formal steps. When a tenant asks for an inspection, the most effective wording is to ask for the property to be assessed for hazards under the council’s housing standards process and for the outcome to be confirmed in writing.

To keep the request aligned with how councils operate, use the government’s overview of how councils deal with housing hazards and enforcement as the reference point for what an assessment and follow-up can look like in practice: GOV.UK guidance.

Evidence that matters

Councils tend to act faster when the evidence shows persistence, impact, and failed attempts to resolve it. The most useful evidence is dated and specific, and it shows the condition in context (for example, mould across a whole wall rather than a close-up that could be anywhere). Written communication with the landlord or agent matters because it shows notice and delay. If there are health impacts, a brief note of symptoms and when they occur can help, but the council usually focuses on the property condition rather than diagnosing health issues.

What not to do is flood the council with dozens of attachments, long narratives, or repeated chasers that add no new information. That can slow triage and make the case look like a dispute rather than a hazard report. One thing that should not be done yet is withholding rent as a tactic to force an inspection; that often creates a separate problem and can distract from getting the hazard assessed.

Useful records

Collect evidence that shows the problem clearly and ties it to dates and rooms. Keep it in a single folder so it can be sent quickly if the council asks for more.

Checklist:

- Photos or short videos with dates, showing the room and the affected area

- A simple timeline of when the problem started and what changed

- Copies of emails/texts/letters to the landlord or agent and any replies

- Notes of missed appointments, access issues, or temporary fixes offered

Common mistakes

These are the errors that most often lead to a stalled or closed case.

- Sending only a general complaint without stating the hazard and the rooms affected

- Relying on a phone call with no follow-up email confirming what was said

- Assuming the council has contacted the landlord when no case reference exists

What to do next

Send written request

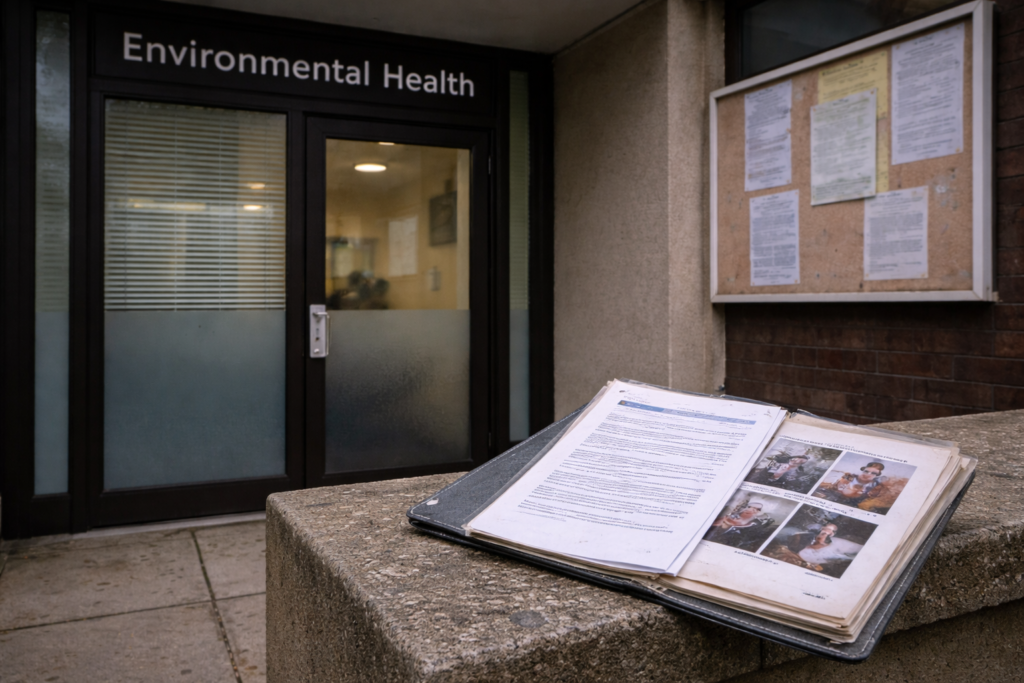

Email the council team that deals with private rented housing standards (often within environmental health) and ask for the complaint to be logged, acknowledged, and assessed for an inspection. Keep it short: property address, who lives there, what the hazard is, which rooms are affected, how long it has been going on, and what the landlord has done so far. Attach a small set of the clearest evidence rather than everything.

Ask for reasons

If the council says it will not inspect, reply asking for the decision in writing, the reason, and what additional information would change the decision. Ask whether the case has been closed and, if so, on what basis. This often turns an informal brush-off into a reviewable decision.

Use official process

Use the council’s official online reporting form or complaints process only, rather than social media messages or informal inboxes, because the form usually creates a case reference and routes it to the correct team. The form is normally found on the council website under “private rented housing”, “housing standards”, or “report a housing problem”. Prepare the information before submitting so the report is complete and does not get parked for “more details”.

Checklist:

- Full address and landlord/agent contact details (if known)

- Clear description of the hazard and the rooms affected

- Dates: when reported to the landlord and what response was received

- Best access times and any access restrictions

The normal response timeframe is an acknowledgement within a few working days and a decision on next steps within a couple of weeks, depending on urgency and local workload. If there is no acknowledgement, escalate by submitting a formal complaint through the council’s complaints procedure, quoting the date of the original report and asking for the housing standards manager to review the refusal or lack of action. If the council keeps treating the issue as “landlord-tenant dispute” despite clear hazards, change strategy by asking for a written hazard assessment outcome and, where relevant, requesting a Council inspection for rental property as a specific service rather than general help.

A typical real UK outcome is that once a case reference exists and the evidence is clear, the council either schedules a visit or sends the landlord a warning letter that prompts repairs.

Know when urgent

If there is immediate danger (for example, exposed live wiring, no safe water, severe structural risk, or carbon monoxide concerns), state that clearly and ask for urgent triage. If the council still refuses to engage, record that refusal in writing and use the council complaints route straight away, because urgency is assessed on what is documented, not what is assumed.

Related issues on this site

If the council will not inspect because the landlord claims access has been offered, it can help to check what counts as reasonable notice and entry, especially where visits are being arranged at short notice or without agreement; the situation often overlaps with Landlord entered property without notice. Where the main hazard is persistent condensation, leaks, or black mould, the evidence and wording that councils respond to can differ from a general repairs complaint, and it may be more effective to frame it using the patterns covered in mould and damp cases.

FAQ

Refusal by email

A council refusal to inspect by email is best handled by asking for the decision criteria and what evidence would trigger a visit. Request a case reference and confirmation whether the case is closed.

Landlord promises repairs

When a landlord promises repairs but nothing changes, councils usually want the timeline and copies of messages showing delay. Ask the council to review the case after a set period if the promised work does not happen.

Access and appointments

Problems with access and appointments often lead to councils pausing action until dates are agreed. Provide two or three realistic time windows and confirm in writing that access will be given.

Health impact notes

Basic health impact notes for damp and mould reports can help show seriousness without turning it into a medical dispute. Keep it factual: symptoms, dates, and which room seems linked.

Before you move on

Put the request back into the council’s system with a logged report, a written refusal if they will not inspect, and a clear escalation point through the council complaints process. Time pressure can build when a landlord pushes for quick access on unsuitable terms or tries to close the issue with a temporary fix.

Get help with the next step

Contact UKFixGuide — Share the council’s refusal wording and the hazard details so the next message can be drafted to trigger a proper review and inspection decision.